Introduction

Hello. I have recently been spending a lot of time dithering. In image processing, dithering is the act of applying intentional perturbations or noise in order to compensate for the information lost during colour reduction, also known as quantisation. In particular, I’ve become very interested in a specific type of dithering and its application to colour palettes of arbitrary or irregular colour distributions. Before going into detail however, let’s briefly review the basics of image dithering.

Dithering in its simplest form can be understood by observing what happens when we quantise an image with and without modifying the source by random perturbation. In the examples below, a gradient of 256 grey levels is quantised to just black and white. Note how the dithered gradient is able to simulate a smooth transition from start to end.

While this is immediately effective, the random perturbations introduce a disturbing texture that can obfuscate details in the original image. To counter this, we can make some smart choices on where and by how much to perturb our input image in an attempt to add some structure to our dither and preserve some of the lost detail.

Ordered Dithering

Instead of perturbing each pixel in the input image at random, we can choose to dither by a predetermined amount depending on the pixel’s position in the image. This can be achieved using a threshold map; a small, fixed-size matrix where each entry tells us the amount by which to perturb the input value

, producing the dithered value

. This matrix is tiled across the input image and sampled for every pixel during the dithering process. The following describes a dithering function for a 4×4 matrix given the pixel raster coordinates

:

We can see that the threshold map distributes perturbations more optimally than purely random noise, resulting in a clearer and more detailed final image. The algorithm itself is extremely simple and trivially parallelisable, requiring only a few operations per pixel.

Error-Diffusion Dithering

Another way to approach dithering is to analyse the input image in order to make informed decisions about how best to perturb pixel values prior to quantisation. Error-diffusion dithering does this by sequentially taking the quantisation error for the current pixel (the difference between the input value and the quantised value) and distributing it to surrounding pixels in variable proportions according to a diffusion kernel . The result is that input pixel values are perturbed just enough to compensate for the error introduced by previous pixels.

Due to this more measured approach, error-diffusion dithering is even better at preserving details and can produce a more organic looking final image. However, the algorithm itself is inherently serial and not easily parallelised. Additionally, the propagation of error can cause small discrepancies in one part of the image to cascade into other distant areas. This is very obvious during animation, where pixels will appear to jitter between frames. It also makes files harder to compress.

Palette Quantisation

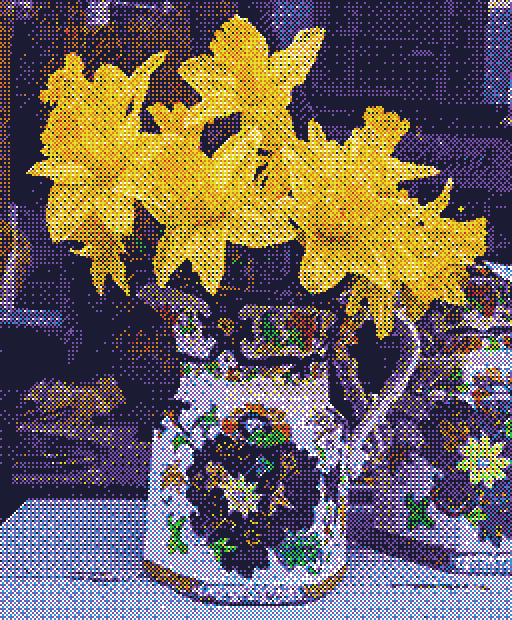

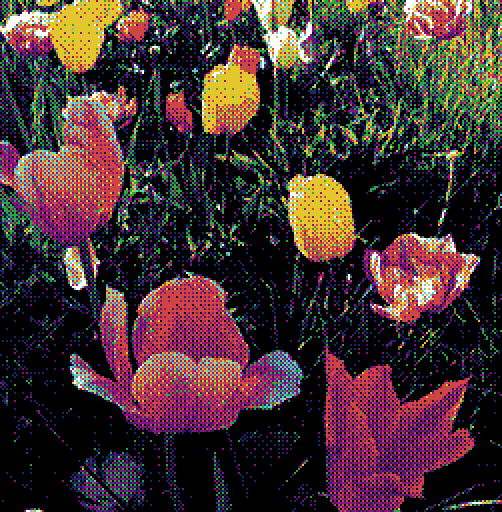

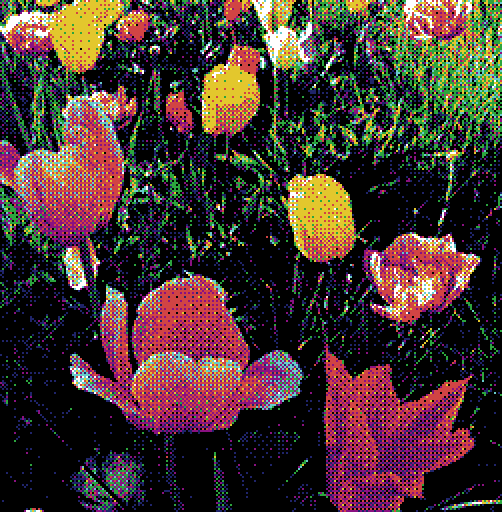

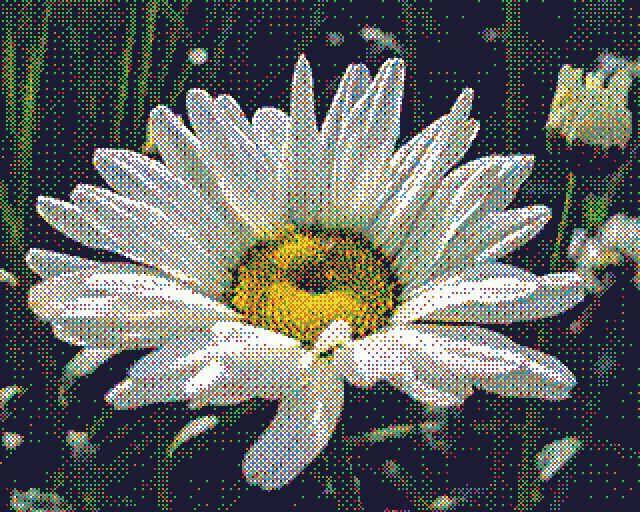

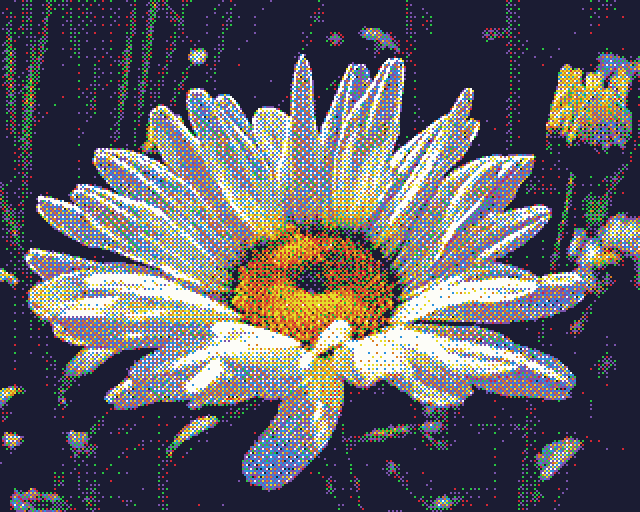

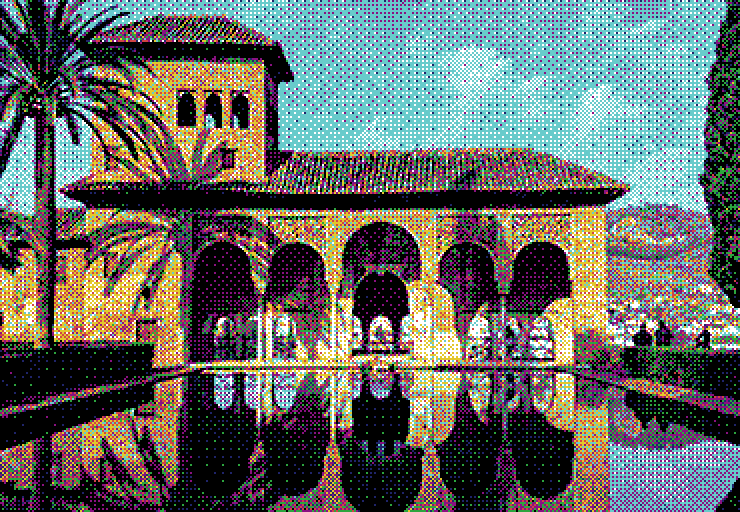

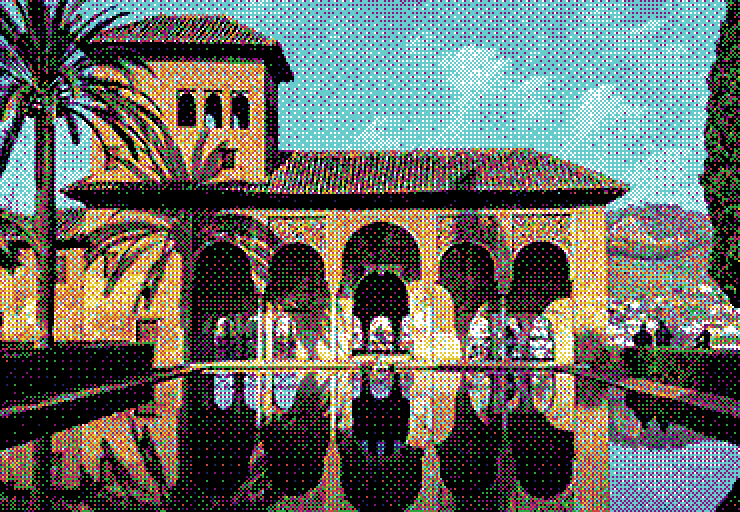

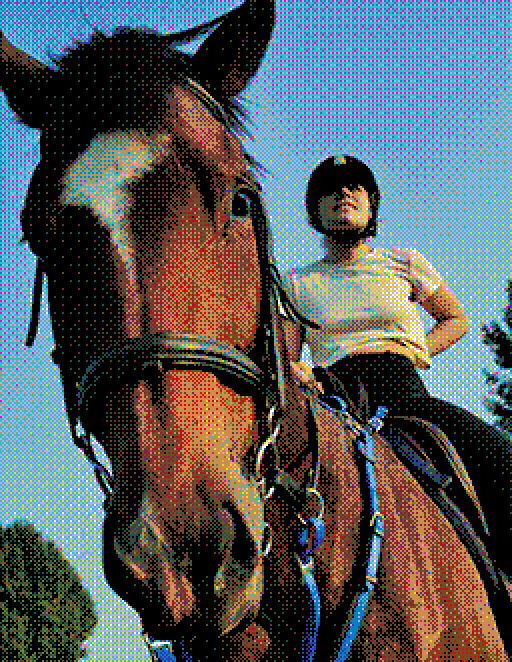

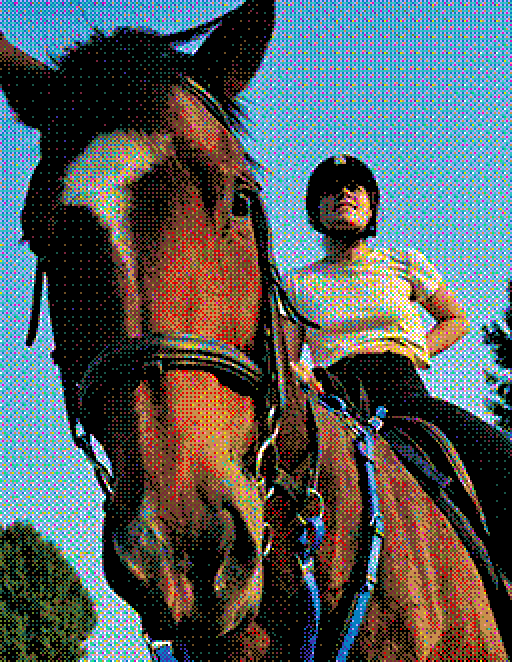

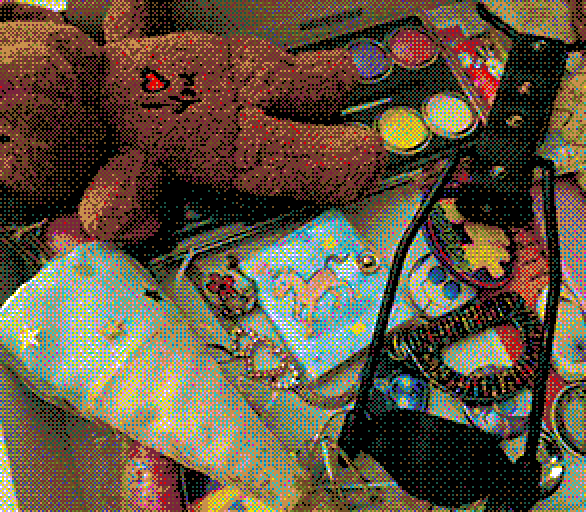

Moving beyond just black and white towards full-colour variable palettes presents another set of problems. Taking the methods presented above and quantising an image using an arbitrary colour palette reveals that error-diffusion is also better at preserving colour information when compared to ordered dithering.

Intuitively, it’s not too difficult to understand why this is the case. Remember that error-diffusion works in response to the relationship between the input value and the quantised value. In other words, the colour palette is already factored in during the dithering process. On the other hand, ordered dithering is completely agnostic to the colour palette being used. Images are perturbed the same way every time, regardless of the given palette.

Regular vs Irregular Palettes

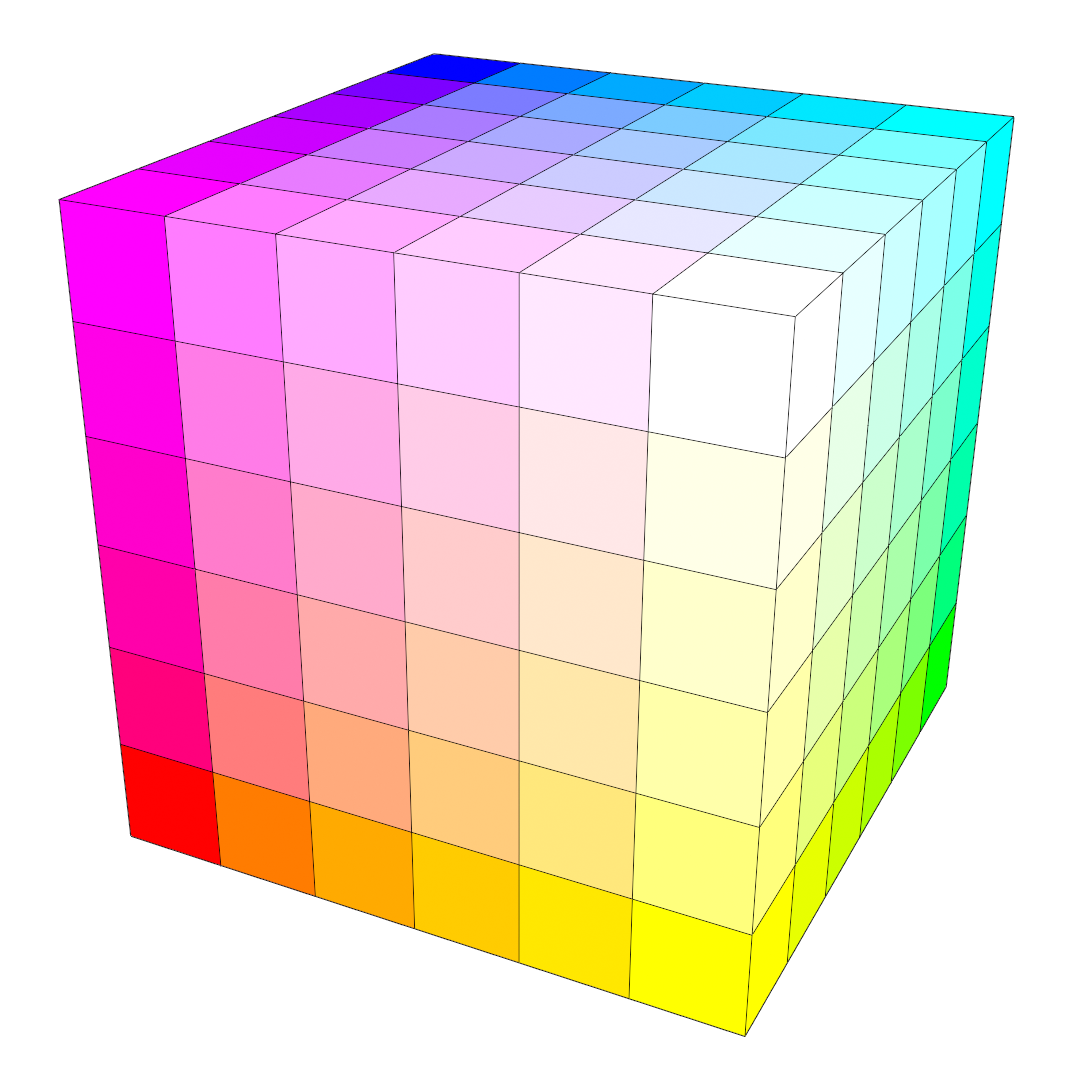

Under certain circumstances, it’s possible to modify ordered dithering so that it can better handle colour information. This requires that we use a palette that is regularly distributed in colour space. A regular palette is composed of all possible combinations of red, green and blue tristimulus values, where each colour component is partitioned into a number of equally spaced levels. For example, 6 levels of red, green and blue totals 6³ = 216 unique colours, equivalent to the common web-safe palette.

This time, before we perturb the input image, we take the value given by the threshold matrix and divide it by , where

is the number of levels for each colour component. As a result, each pixel is perturbed just enough to cover the minimal distance between two colours in the palette. Since the entire palette is evenly distributed across colour space, we only need to modify the range of perturbation along each axis. The dithering equation then becomes:

The whole algorithm can be expressed in psuedocode like so:

for each pixel in image

let value = value in threshold matrix at (x, y)

let offset = pixel + (value - 0.5) * (1.0 / number of levels)

set pixel as closest colour to offset

By appropriately scaling the perturbation amount for each colour channel separately, we can also extend this to work with palettes where is different for each colour component, provided that they are still regularly spaced. Unfortunately, the less regular the palette is, the less effective this technique becomes. If we wish to leverage the strengths of ordered dithering for use with irregular or arbitrary palettes, a more general solution is needed.

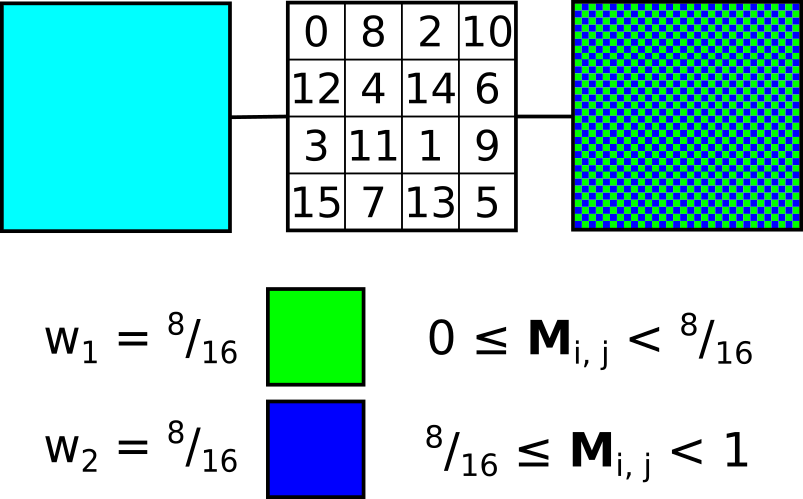

The Probability Matrix

Another way to look at our threshold matrix is as a kind of probability matrix. Instead of offsetting the input pixel by the value given in the threshold matrix, we can instead use the value to sample from the cumulative probability of possible candidate colours, where each colour

is assigned a probability or weight

. Each colour’s weight represents it’s proportional contribution to the input colour. Colours with greater weight are then more likely to be picked for a given pixel and vice-versa, such that the local average for a given region should converge to that of the original input value. We can call this the N-candidate approach to palette dithering.

This approach shares a lot in common with the idea of multivariate interpolation over scattered data. Multivariate interpolation attempts to estimate values at unknown points within an existing data set and is often used in fields such as geostatistics or for geophysical analysis like elevation modelling. We can think of our colour palette as the set of variables we want to interpolate from, and our input colour as the unknown we’re trying to estimate. We can borrow some ideas from multivariate interpolation to develop more effective dithering algorithms.

N-Closest Algorithm

The N-closest or N-best dithering algorithm is a straightforward solution to the N-candidate problem. As the name suggests, the set of candidates is given by the closest palette colours to the input pixel. To determine their weights, we simply take the inverse of the distance to the input pixel. This is essentially the inverse distance weighting (IDW) method for multivariate interpolation, also known as Shepard’s method. The following pseudocode sketches out a possible implementation:

for each pixel in image

let sum of weights = 0.0

let list of candidates = N closest colours to pixel

for each candidate in list of candidates

candidate.weight = 1.0 / distance to candidate

sum of weights += candidate.weight

for each candidate in list of candidates

candidate.weight /= sum of weights

let seed = value in threshold matrix at (x, y)

let sum = 0.0

for each candidate in list of candidates

sum += candidate.weight

if seed < sum

set pixel as candidate

process next pixelOne by-product of weighing the candidates by their distance is that the resulting output image is prone to false contours or banding. Increasing reduces this effect at the cost of added granularity or high frequency noise due to the introduction of ever more distant colours to the set. I recommend taking a look at the original paper if you’re interested in learning a bit more about the algorithm[1].

Note that IDW often includes a variable exponent that is applied to the distance before taking the inverse. For a given distance

, the weight

of the candidate becomes:

As you might expect, the result of this is that colours which lie closer to the input pixel are given a greater proportion of the total influence with ever-increasing values of . This is not mentioned in the cited paper but it might be nice to consider for your own implementation.

N-Convex Algorithm

Instead of taking the nearest candidates to

, we can look for a set of

candidates whose centroid is close to

. The N-convex algorithm works by finding the closest colour to a given target colour for

iterations, where the target is first initialised to be equal to the input pixel. Every iteration the closest colour added to the candidate list, and the quantisation error between it and the original input pixel is added to the target.

for each pixel in image

let goal = pixel

do n times

candidate[n] = closest colour to goal

mark candidate[n] as used

goal += pixel - candidate[n]If this sounds familiar to you, it’s because this method works very similarly to error-diffusion. Instead of letting adjacent pixels compensate for the error, we’re letting each successive candidate compensate for the combined error of all previous candidates.

Like the N-closest algorithm, the weight of each candidate is given by the inverse of its distance to the input colour. Because of this, both algorithms produce output of a similar quality, although the N-convex method is measurably faster. As with the last algorithm, more details can be found in the original paper[2].

The Linear Combination

If we think about this algebraically, what we really want to do is express the input pixel as the weighted sum of palette colours. This is nothing more than a linear combination of palette colours

with weights

:

Note however that depending on as well as the distribution of colours in the palette, there may not always be an exact solution for any given

. Instead we’ll say that we want to minimise the absolute error between

and some linear combination

, or

.

As it stands, inverse distance weighting is not very good at minimising this error. Another approach is needed if we want to improve the image quality.

Thomas Knoll’s Algorithm

Like the N-convex algorithm, this algorithm attempts to find a set of candidates whose centroid is close to . The key difference is that instead of taking

unique candidates, we allow candidates to populate the set multiple times. The result is that the weight of each candidate is simply given by its frequency in the list, which we can then index by random selection:

for each pixel in image

let goal = pixel

do n times

candidate[n] = closest colour to goal

goal += pixel - candidate[n]

let seed = random integer from 0 to n

set pixel as candidate[seed]This algorithm attempts to minimise numerically. Because of this, the quality of the dither produced by Knoll’s algorithm is much higher than any other of the N-candidate methods we have covered so far. It is also the slowest however, as it requires a greater

per-pixel to be really effective. More details are given in Knoll’s now expired patent[3]. I have put together a GPU implementation of Knoll’s algorithm on Shadertoy here.

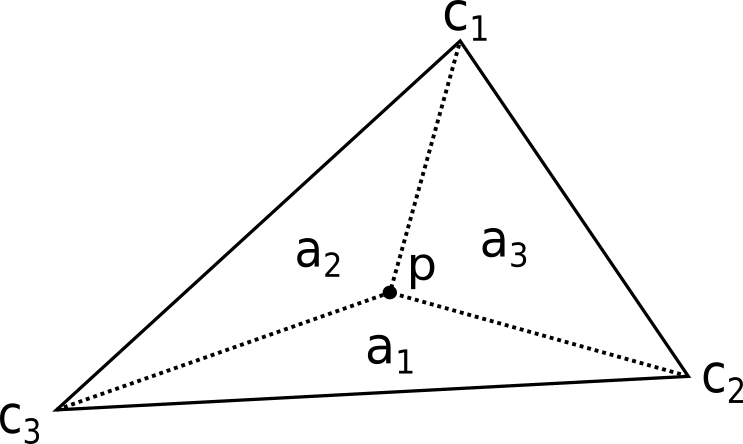

Barycentric Coordinates

Another way to approach the linear combination is to look at it geometrically. This is where the idea of barycentric coordinates can help. A barycentric coordinate system describes the location of a point as the weighted sum of the regular coordinates of the vertices forming a simplex. In other words, it describes a linear combination with respect to a set of points, where

in

-dimensional space.

The weight of each term is given by the proportion of each sub-triangle area with respect to the total triangle area

. Algebraically, this can be expressed like so:

Knowing this, we can modify the N-Convex algorithm covered earlier such that the candidate weights are given by the barycentric coordinates of the input pixel after being projected onto a triangle whose vertices are given by three surrounding colours, abandoning the IDW method altogether1. This results in a fast and exact minimisation of , with the final dither being closer in quality to that of Knoll’s Algorithm.

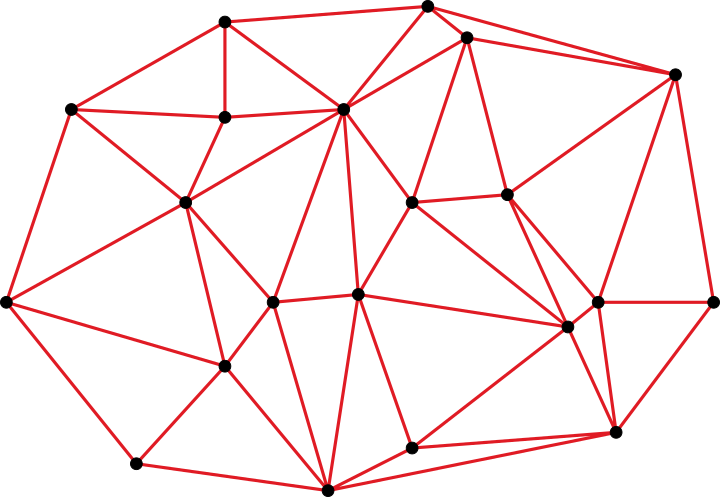

Triangulated Irregular Network

Recall that a barycentric coordinate system is given with respect to a -dimensional simplex, where

is no larger than the dimensional space. Given a set of scattered points, it’s possible to create a tessellation of the space by forming simplices from the points, such that any input point that lies within the convex hull of the scattered set can be expressed in terms of the enclosing simplex and its corresponding barycentric coordinates2. This can be understood as a kind of triangulated irregular network (TIN).

While there exist many possible ways to triangulate a set of points, the most common method for TINs is the Delaunay triangulation. This is because Delaunay triangulations tend to produce more regular tessellations that are better suited to interpolation. In theory, we can represent our colour palette as a TIN by computing the 3D Delaunay triangulation of the colours in colour space. The nice thing about this is that it makes finding an enclosing simplex much faster; the candidate selection process is simply a matter of determining the enclosing tetrahedron of an input point within the network using a walking algorithm, and taking the barycentric coordinates as the weights.

If executed well, Delaunay-based tetrahedral dithering can outperform the N-convex method and produce results that rival Knoll’s algorithm. The devil is in the detail however, as actually implementing a robust Delaunay triangulator is a non-trivial task, especially where numerical stability is concerned. The additional memory overhead required by the triangulation structure may also be a concern.

Natural Neighbour Interpolation

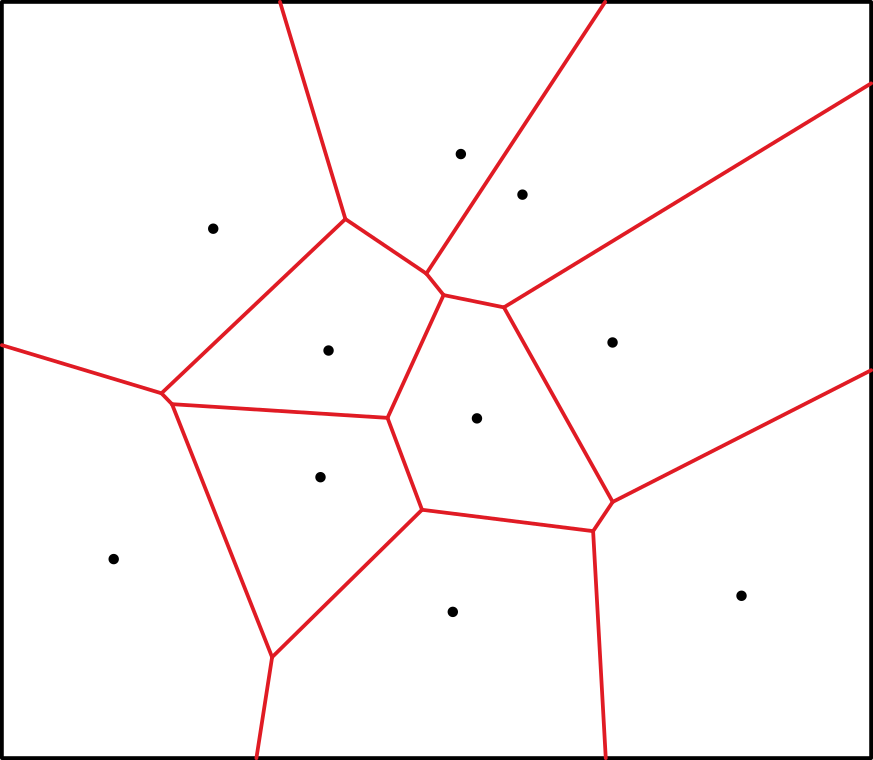

We’ve looked at how we can geometrically find the linear combination using barycentric coordinates, but it is not the only way to do so. Natural neighbour interpolation works by observing what happens when an input point is inserted into a set of points represented by a Voronoi diagram. The Voronoi diagram is simply a partition of space into polygonal regions for each data point, such that any point inside a given region is proximal to its corresponding data point.

When another data point is inserted and the Voronoi diagram reconstructed, the newly created region displaces the area that once belonged to the old regions. Those points whose regions were displaced are considered natural neighbours to the new point. The weight of each natural neighbour is given by the area taken from the total area

occupied by the new region. In 3D, we measure polyhedral volumes instead of areas.

Natural neighbour interpolation has a number of strengths over linear barycentric interpolation. Namely, it provides a smooth or continuous slope between samples3, and is always the same for a given point set, unlike the TIN where the quality of the triangulation can produce biases in the outcome, even in the best case.

Implementing natural neighbour interpolation implies the construction of a geometric Voronoi diagram, however this is not strictly the case. Since the Delaunay triangulation is the dual graph of the Voronoi diagram, all the information needed to perform natural neighbour interpolation is already implicit within the triangulation itself. Algorithms to determine natural neighbours from the Delaunay triangulation can be found in several papers within the literature[4][5]. Unfortunately the relative complexity of natural neighbour interpolation means that it is slower than barycentric interpolation by a considerable margin.

Joel Yliluoma’s Algorithms

A notable resource on the topic of ordered dithering using arbitrary palettes is Joel Yliluoma’s Arbitrary-Palette Positional Dithering Algorithm. One key difference of Yliluoma’s approach is in the use of error metrics beyond the minimisation of . Yliluoma notes that the perceptual or psychovisual quality of the dither must be taken into account in addition to its mathematical accuracy. This is determined by use of some cost function which considers the relationship between a set of candidate colours. The number of candidates, the particular cost function, and the thoroughness of the selection process itself give rise to a number of possible implementations, each offering varying degrees of quality and time complexity.

Yliluoma’s algorithms can produce very good results, with some variants matching or even exceeding that of Knoll’s. They are generally slower however, except in a few cases.

Tetrapal: A Palette Triangulator

Most of the algorithms described here are quite straightforward to implement. Some of them can be written in just a few lines of code, and those that require a bit more effort can be better understood by reading through the relevant papers and links I have provided. The exception to this are those that rely on the Delaunay triangulation to work. Robust Delaunay triangulations in 3D are fairly complex and there isn’t any publicly available software that I’m aware of that leverages them for dithering in the way I’ve described.

To this end, I have written a small C library for the sole purpose of generating the Delaunay triangulation of a colour palette and using the resulting structure to perform barycentric interpolation as well as natural neighbour interpolation for use in colour image dithering. The library and source code is available for free on Github. I’ve included an additional write up that goes into a bit more detail on the implementation and also provides some performance and quality comparisons against other algorithms. Support would be greatly appreciated!

Appendix I: Candidate Sorting

When using the probability matrix to pick from the candidate set, it is important that the candidate array be sorted in advance. Not doing so will fail to preserve the patterns distinctive of ordered dithering. A good approach is to sort the candidate colours by luminance, or the measure of a colour’s lightness4. When this is done, we effectively minimise the contrast between successive candidates in the array, making it easier to observe the pattern embedded the matrix.

If the number of candidates for each pixel grows too large (as is common in algorithms such as Knoll and Yliluoma) then sorting the candidate list for every pixel can have a significant impact on performance. A solution is to instead sort the palette in advance and keep a separate tally of weights for every palette colour. The weights can then be accumulated by iterating linearly through the tally of sorted colours.

sort palette by luminance

let weights[palette size] = weight for each colour

...

for i in range 0 to palette size - 1

cumulative weight += weights[i]

if cumulative weight < probability value

set pixel as palette[i]Appendix II: Linear RGB Space

Most digital images intended for viewing are generally assumed to be in sRGB colour space, which is gamma-encoded. This means that a linear increase of value in colour space does not correspond to a linear increase in actual physical light intensity, instead following more of a curve. If we want to mathematically operate on colour values in a physically accurate way, we must first convert them to linear space by applying gamma decompression. After processing, gamma compression should be reapplied before display. The following C code demonstrates how to do so following the sRGB standard:

void srgb_to_linear(float pixel[3])

{

pixel[0] = pixel[0] > 0.04045f ? powf((pixel[0] + 0.055f) / 1.055f, 2.4f) : pixel[0] / 12.92f;

pixel[1] = pixel[1] > 0.04045f ? powf((pixel[1] + 0.055f) / 1.055f, 2.4f) : pixel[1] / 12.92f;

pixel[2] = pixel[2] > 0.04045f ? powf((pixel[2] + 0.055f) / 1.055f, 2.4f) : pixel[2] / 12.92f;

}

void linear_to_srgb(float pixel[3])

{

pixel[0] = pixel[0] > 0.0031308f ? 1.055f * powf(pixel[0], 1.0f / 2.4f) - 0.055f : 12.92f * pixel[0];

pixel[1] = pixel[1] > 0.0031308f ? 1.055f * powf(pixel[1], 1.0f / 2.4f) - 0.055f : 12.92f * pixel[1];

pixel[2] = pixel[2] > 0.0031308f ? 1.055f * powf(pixel[2], 1.0f / 2.4f) - 0.055f : 12.92f * pixel[2];

}

Appendix III: Threshold Matrices and Noise Functions

All of the examples demonstrating ordered dithering so far have been produced using a specific type of threshold matrix commonly known as a Bayer matrix. In theory however any matrix could be used and a number of alternatives are available depending on your qualitative preference. Matrices also don’t have to be square or even rectangular; polyomino-based dithering matrices have been explored as well[6].

The classic Bayer or ‘dispersed-dot’ pattern arranges threshold values in an attempt to optimise information transfer and minimise noise[7]. The matrix dimensions are typically a power of two. The following values describe an 8×8 matrix:

int bayer_matrix[8][8] = {

{ 0, 32, 8, 40, 2, 34, 10, 42 },

{ 48, 16, 56, 24, 50, 18, 58, 26 },

{ 12, 44, 4, 36, 14, 46, 6, 38 },

{ 60, 28, 52, 20, 62, 30, 54, 22 },

{ 3, 35, 11, 43, 1, 33, 9, 41 },

{ 51, 19, 59, 27, 49, 17, 57, 25 },

{ 15, 47, 7, 39, 13, 45, 5, 37 },

{ 63, 31, 55, 23, 61, 29, 53, 21 } };

The halftone or ‘clustered-dot’ matrix uses a dot pattern reminiscent of traditional photographic halftoning. Here a diagonal variant of the pattern is given:

int halftone_matrix[8][8] = {

{ 24, 10, 12, 26, 35, 47, 49, 37 },

{ 8, 0, 2, 14, 45, 59, 61, 51 },

{ 22, 6, 4, 16, 43, 57, 63, 53 },

{ 30, 20, 18, 28, 33, 41, 55, 39 },

{ 34, 46, 48, 36, 25, 11, 13, 27 },

{ 44, 58, 60, 50, 9, 1, 3, 15 },

{ 42, 56, 62, 52, 23, 7, 5, 17 },

{ 32, 40, 54, 38, 31, 21, 19, 29 } };

The blue noise or ‘void-and-cluster’ dither pattern avoids directional artefacts while retaining the optimal qualities of the Bayer pattern. The Bayer matrix can in fact be derived from the void-and-cluster generation algorithm itself[8].

You can access some tiled blue noise textures in plain text format here. I have also released a small C library for generating these textures.

It’s also possible to abandon the threshold matrix altogether and instead calculate a value for every pixel coordinate at runtime. If the function is simple enough this can be a good and efficient way to break up patterns and create interesting textures.

White noise simply uses a random number generator to produce threshold values.

float white_noise(int x, int y)

{

return (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

}

Interleaved gradient noise is a form of low-discrepancy sequence that attempts to distribute values more evenly across space when compared to pure white noise[9].

float interleaved_gradient_noise(int x, int y)

{

return fmodf(52.9829189f * fmodf(0.06711056f * (float)x + 0.00583715f * (float)y, 1.0f), 1.0f);

}

The R-sequence is another type of low-discrepancy sequence based on specially chosen irrational numbers[10]. It is similar to interleaved gradient noise but is simpler to compute and possibly more effective as a dither, particularly when augmented with a triangle wave function as demonstrated:

float r_sequence(int x, int y)

{

float value = fmodf(0.7548776662f * (float)x + 0.56984029f * (float)y, 1.0f);

return value < 0.5f ? 2.0f * value : 2.0f - 2.0f * value;

}

Footnotes

1 It’s also possible to use 4 candidates per pixel and compute the barycentric coordinates of the resulting tetrahedron, but using 3 candidates forming a triangle is more straightforward. ↑

2 For points outside the convex hull, an acceptable solution is to find the closest point on the surface and determine the barycentric coordinates for that point instead. ↑

3 Strictly speaking, the slope is continuous everywhere except for the data points themselves. ↑

4 A good discussion on luminance and how to calculate it can be found on this stack exchange question. ↑

References

[1] K. Lemström, J. Tarhio & T. Takala: “Color Dithering with n-Best Algorithm” (1996). ↑

[2] K. Lemström & P. Fränti: “N-Candidate methods for location invariant dithering of color images” (2000). ↑

[3] T. Knoll: “Pattern Dithering” (1999). US Patent No. 6,606,166. ↑

[4] M. Sambridge, J. Braunl & H. McQueen: “Geophysical parametrization and interpolation of irregular data using natural neighbours” (1995). ↑

[5] L. Liang & D. Hale: “A stable and fast implementation of natural neighbour

interpolation” (2010). ↑

[6] D. Vanderhaeghe & V. Ostromoukhov: “Polyomino-Based Digital Halftoning” (2008). ↑

[7] B. E. Bayer: “An optimum method for two-level rendition of continuous-tone pictures” (1973). ↑

[8] R. Ulichney: “The void-and-cluster method for dither array generation” (1993). ↑

[9] J. Jimenez: “Next Generation Post Processing in Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare” (2014). ↑

[10] M. Roberts: “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Quasirandom Sequences” (2018). ↑