In this short post I want to explore a simple and hopefully intuitive geometric interpretation of a common vector operation; the 3D cross product.

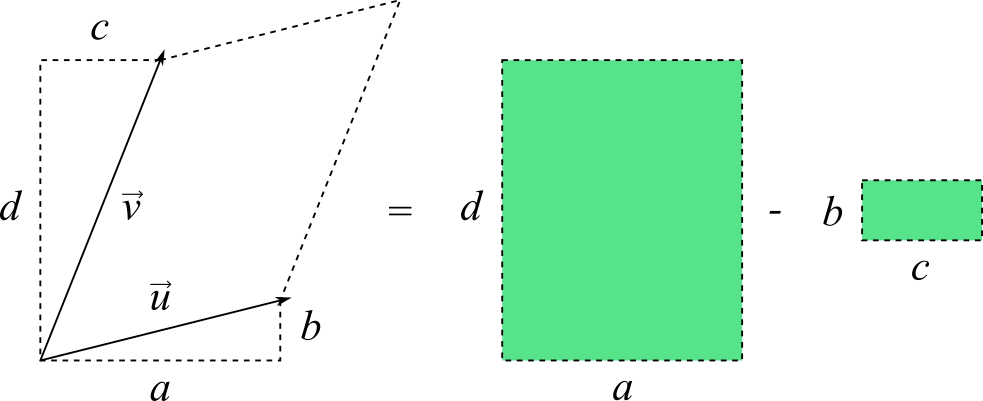

We’ll start by breaking down a somewhat related operation in 2D, sometimes called the perpendicular dot product or just perp dot product. It describes the area of a parallelogram spanned by two vectors

and

, and is given by the determinant of a 2×2 matrix:

One way to interpret this is that we are subtracting the area of the rectangle from the area of rectangle

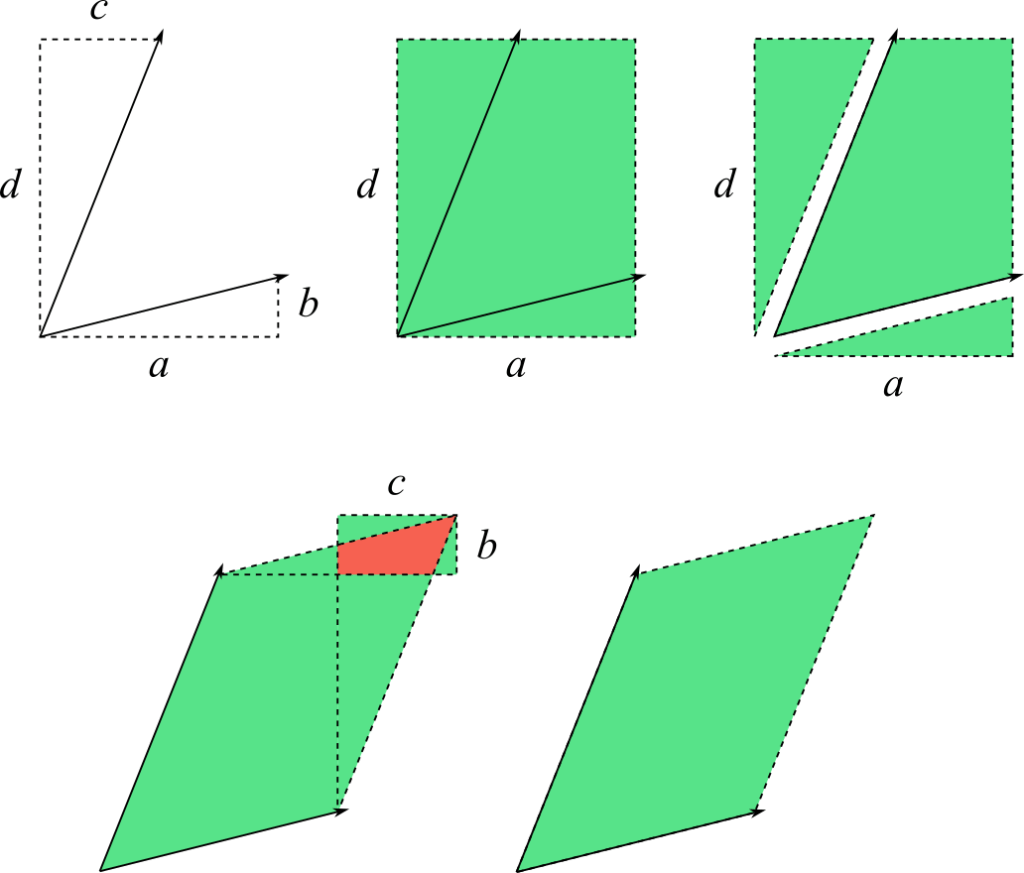

We can put together a simple visual proof by cutting out and rearranging portions of the larger rectangle to show that the smaller rectangle simply cancels out the extra and overlapping areas:

Notice that the area of a triangle with two sides given by the vectors and

is exactly half the area of the associated parallelogram. We’ll revisit this property soon.

In Three Dimensions

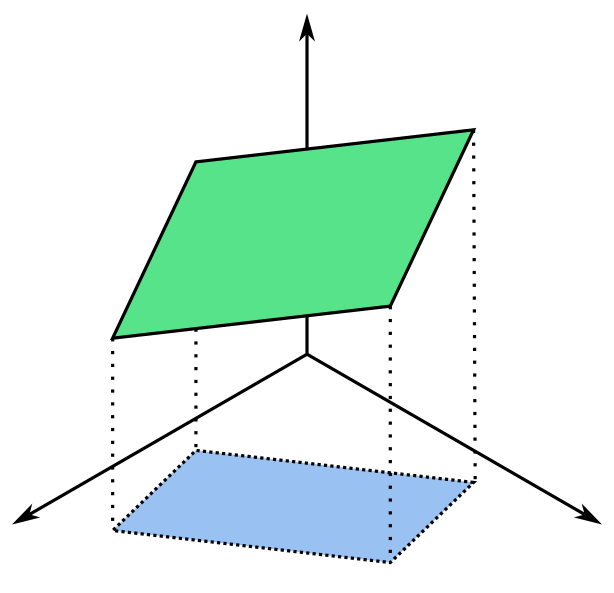

We can take the geometric interpretation of the perp dot product to get a more intuitive understanding of the 3D cross product, albeit with a few more steps. The cross product of two vectors and

returns another vector whose magnitude describes the area

of the parallelogram spanned by

and

in

:

Notice that the cross product operation can be interpreted as three separate perp dot products describing the projection of our original parallelogram onto each of the three coordinate planes. For example, the operation gives the area of the original parallelogram after being projected onto the

plane.

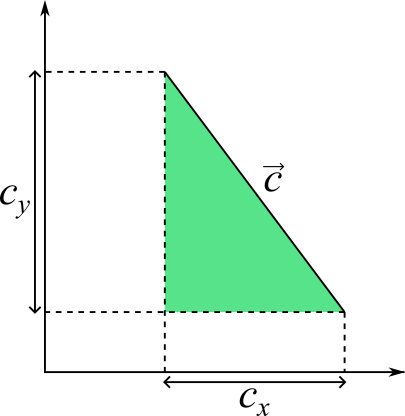

The next step is to intuit what it means to take the magnitude of a vector whose components represent the areas of these projected parallelograms. Recall the formula for taking the magnitude of a 3D vector :

This looks like the formula for Euclidean distance, which is derived from the Pythagorean theorem most of us are familiar with. Just to quickly recap, Pythagoras’ theorem states that the squared length of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is given by the sum of squared lengths of the legs,

and

.

Or, in terms of the length :

If we choose to express as a 2D vector

, notice how the projection of

onto each of the two coordinate axes themselves form a right angled triangle.

Thus, by the Pythagorean theorem:

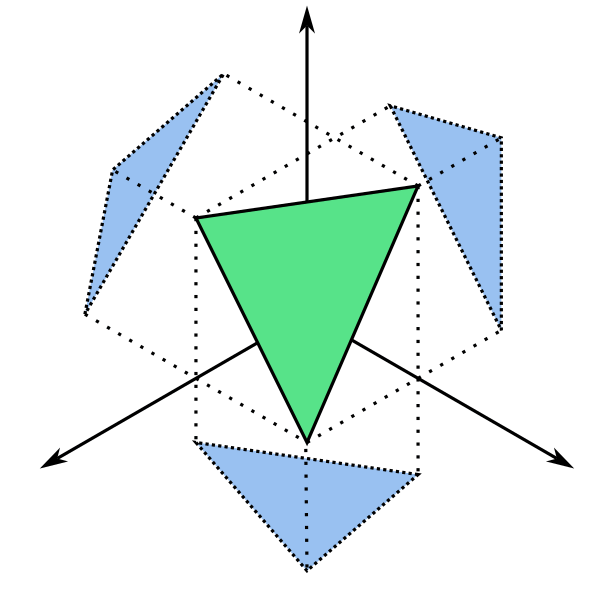

It turns out that this actually generalises to higher dimensions. If we take a triangle in 3D, project it onto each of the three coordinate planes and find the area of each projected triangle, the sum of squares of those areas is equal to the squared area of the original triangle!

We can show that this is true by taking what we know about the perp dot product and Pythagoras’ theorem to get the area of a parallelogram just as we would by using the cross product. Let be a triangle in

which we express in terms of two vectors representing the edges

and

. Earlier we established that the area of a triangle is half that of its associated parallelogram, which can be found by using the perp dot product for a parallelogram in

. Take the area of each triangle resulting from the projection of

onto each coordinate plane and plug them into Pythagoras’ theorem:

We can factor and simplify to take the term out of the square root:

Which we find is equivalent to the following according to the definition of the cross product:

Double the result and you have the area of the parallelogram spanned by and

.